Spikiness

I have recently had opportunities to have conversations with a wide range of people, from experts in workforce development, to academics driving the conversation around diversity and inclusion, to fellow neurodivergents. These conversations have revealed that it is quite hard to find people who are familiar with a key concept in understanding, educating, and working with, neurodivergent people. This is the concept of the spiky skills profile.

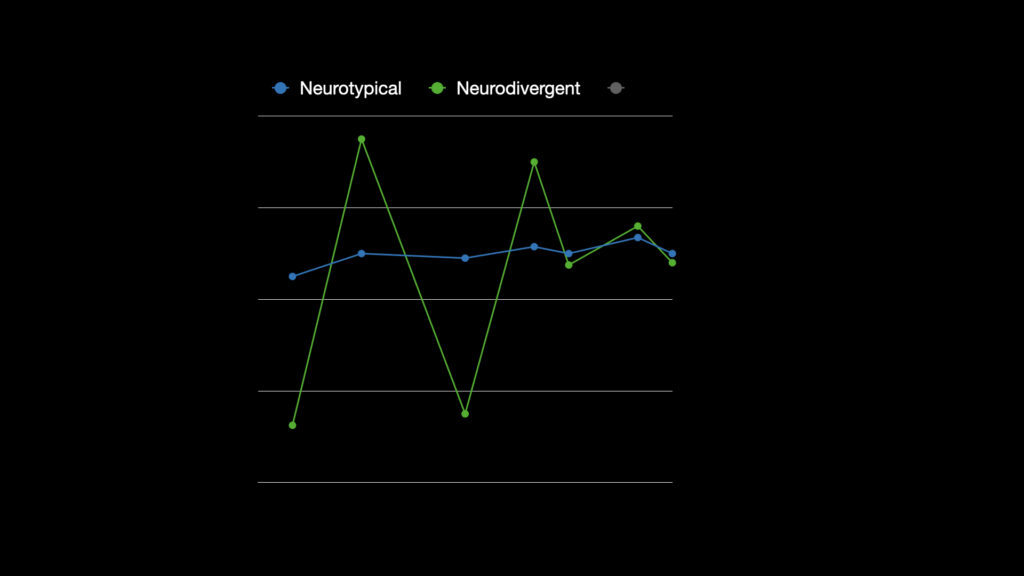

As a general rule, neurotypical (by which I simply mean non-neurodivergent) people, when evaluated across a set of common skills, will have consistent scores among those skills. For example, a test of someone’s ‘verbal’ skills using written evaluation (such as the SAT ‘verbal’ score in America) is assumed to also give a good estimate of that person’s spoken skills. The ability to solve logic puzzles quickly is assumed by some to correlate with the ability to think quickly during a conversation. Furthermore, because there is an assumption that skills profile are flat, the ability to think quickly is assumed to correlate with skills such as the ability to prioritise tasks, and manage one’s time. As a general rule, few if any of these correlations will apply to neurodivergent people.

Illustration of how Neurotypical and Neurodivergent skills profiles differ from each other.

This difference in skills profiles is one of the most profound differences between neurodivergent people and neurotypical people. This is important not just because educational goals, job descriptions, and performance criteria are almost exclusively based on the neurotypical model, but because people are conditioned to make assumptions about others based on the neurotypical model being ‘correct’ and the neurodivergent model being ‘defective.’

It is fairly common for neurodivergent people to be labelled as “lazy” or “not trying.” We also often get pigeon-holed as having bad attitudes, or lacking motivation. One of the complications is that when others assume that a skills profile is flat, there is a tendency to assume that all of our skills are near the level of the greatest weakness. As a result strengths are not just missed, but dismissed.

When used correctly, largely by allowing us to work to our strengths and having others on a team compensate for our weaknesses, neurodivergent people can make a team not just happier, but more productive. I like to suggest that people think of neurodivergent success in the workplace being a form of symbiosis. We contribute different ways of thinking and creativity. Some of us also have strengths which are quite strong, possibly superior, even when measured against the strongest of our neurotypical peers. You can help us effectively harness our strengths and ensure that when we have good ideas they get effectively communicated. We all benefit.

When we get seen as different, and that difference is seen as a positive, we can be tremendous assets. When we are viewed as lacking or defective, or simply evaluated as if we are just like everyone else, we get marginalised and you lose the chance to benefit from our abilities. Don’t ask “why is this person bad at something I would have assumed they would be strong in.” Do ask “how can we support this person working to their strengths in a way which makes their whole team stronger.”

Reasonable and insightful. Thanks.